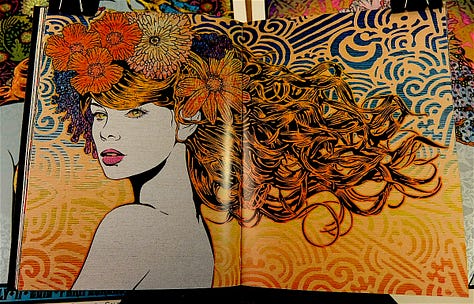

HELIKON HATH NO FURY LIKE A MUSE SCORNED

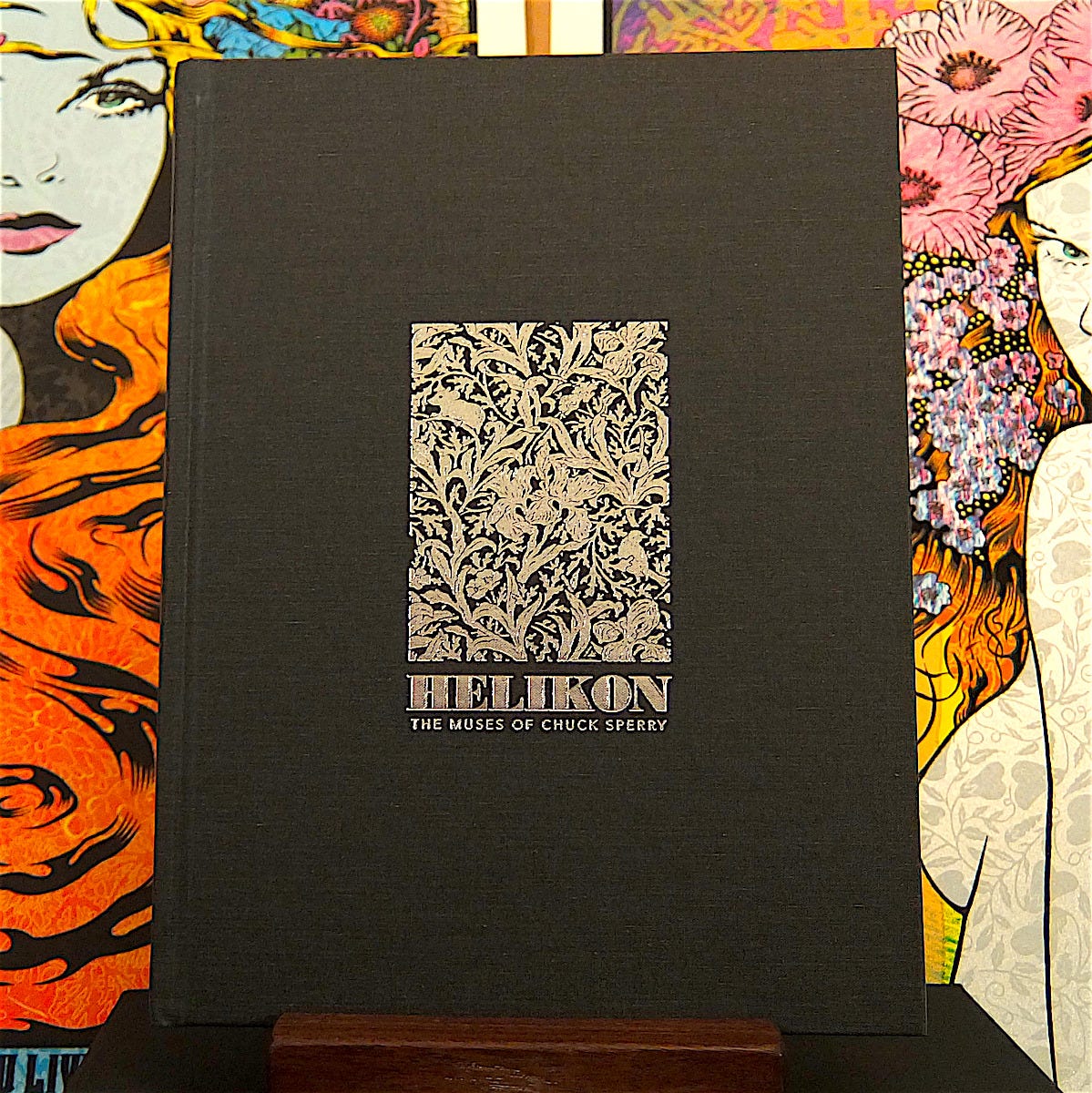

Helikon, The Muses of Chuck Sperry

by Chuck Sperry, Foreward by Charles Bock

Hangar 18

2017, 136 pages, 9.0 x 12.0 inches, Hardcover

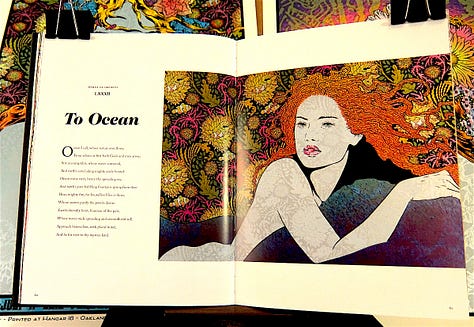

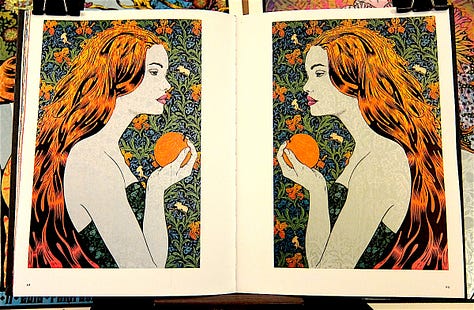

It’s a familiar sight at Widespread Panic, Black Keys, Umphrey’s McGee, Pearl Jam, and Dave Matthews concerts — a crush of people, mostly guys, some with poster tubes slung over their shoulders, crowding around the merch booth even before taking their seats, hoping to score the latest limited-edition screen print of a fetching, scantily clad babe by artist Chuck Sperry. A few years back, Sperry’s “ladies,” as these pieces are known among some rock-poster collectors, were likely mistaken for multi-colored updates of the hippie chicks that occasionally populated the 1960s psychedelic Fillmore and Avalon posters of Wes Wilson, Stanley Mouse, and the late Alton Kelley. Those artists often took their inspiration from Art Nouveau-era legends like Alphonse Mucha and Jules Cheret, and Sperry’s ladies certainly mine that territory, too. But according to a gorgeous and meditative self-published monograph titled Helikon, Sperry’s muses go back much further than the late 19th century, by a factor of a few thousand years.

Posing in little more than their flowing hair, amid flowers, stars, and damask backgrounds whose patterns also adorn their silver flesh, Sperry’s muses take their names from the Orphic Hymns, which were composed as long ago as the third century B.C. In Helikon, which takes its name from the mountain in Greece where the impact of Pegasus’s hooves are said to have created the springs that gave birth to the three original muses, Sperry pairs photographs of his beauties, printed on oak or birch panels, with their corresponding Orphic Hymns, song lyrics by English rocker Nick Cave, and poems by Ovid, Homer, and Hesiod, along with a few more contemporary sources. The resulting mood is as far removed as it could be from the bedlam at the merch booth. Instead, we are invited to linger and read — God help us — the ancient poetry that has inspired Sperry’s work.

Reading this book about images, it turns out, is important, though not unconditionally. For example, in his foreword to Helikon, Charles Bock begins with this probably accurate prediction: “Odds are, you won’t read this.” In the scheme of things, skipping Bock’s intro won’t be the end of the world, whereas not reading the poems and prose accompanying Sperry’s muses would be a major mistake. Poems take time to read, and longer to digest. Some must be read more than once, and none can be read while multitasking. In Helikon, the words transport us, allowing us to see Sperry’s work through fresh, yet ancient, eyes. Importantly, they drive from our minds thoughts of the transitory — that Tethys was first introduced to the world as a Dave Matthews poster; that Artemis and Naiad made their debuts before fans of the Black Keys; that Olympia, Daphne, Semele, and Thalia were Panic ladies before they were Sperry’s muses. “Impatient of yoke, the name of bride, She shuns, and hates the joys, she never try’d,” Ovid tells us of Daphne. Somehow, “Widespread Panic, Tedeschi Trucks Band, Jerry Joseph. Friday, June 20, 2014, Chicago, Illinois. FirstMerit Bank Pavilion at Northerly Island” doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

– Ben Marks

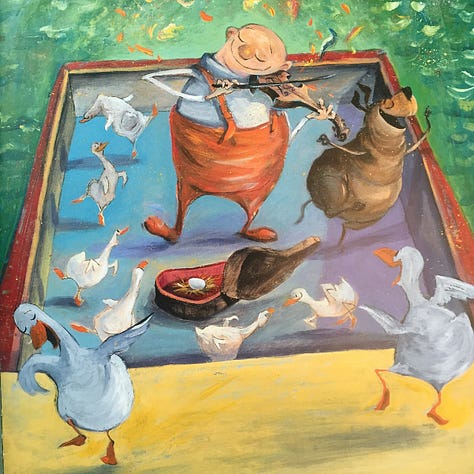

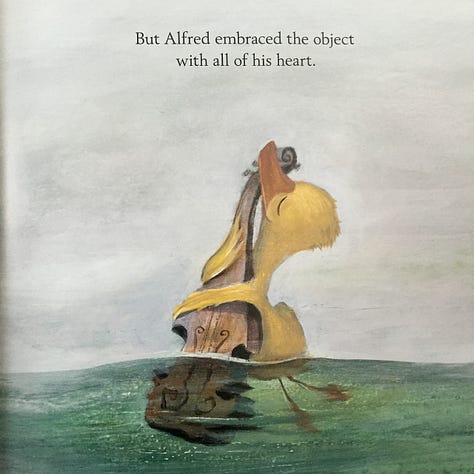

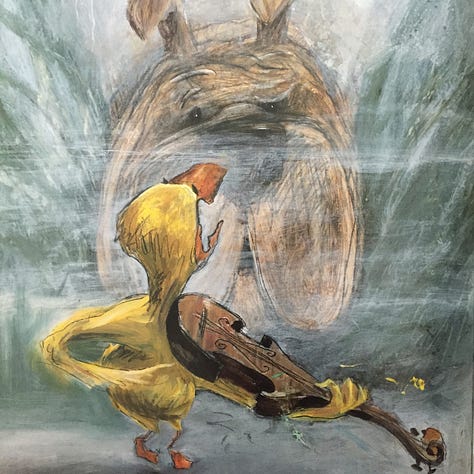

A NEWLY HATCHED DUCKLING IMPRINTS ON A FIDDLE — EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED

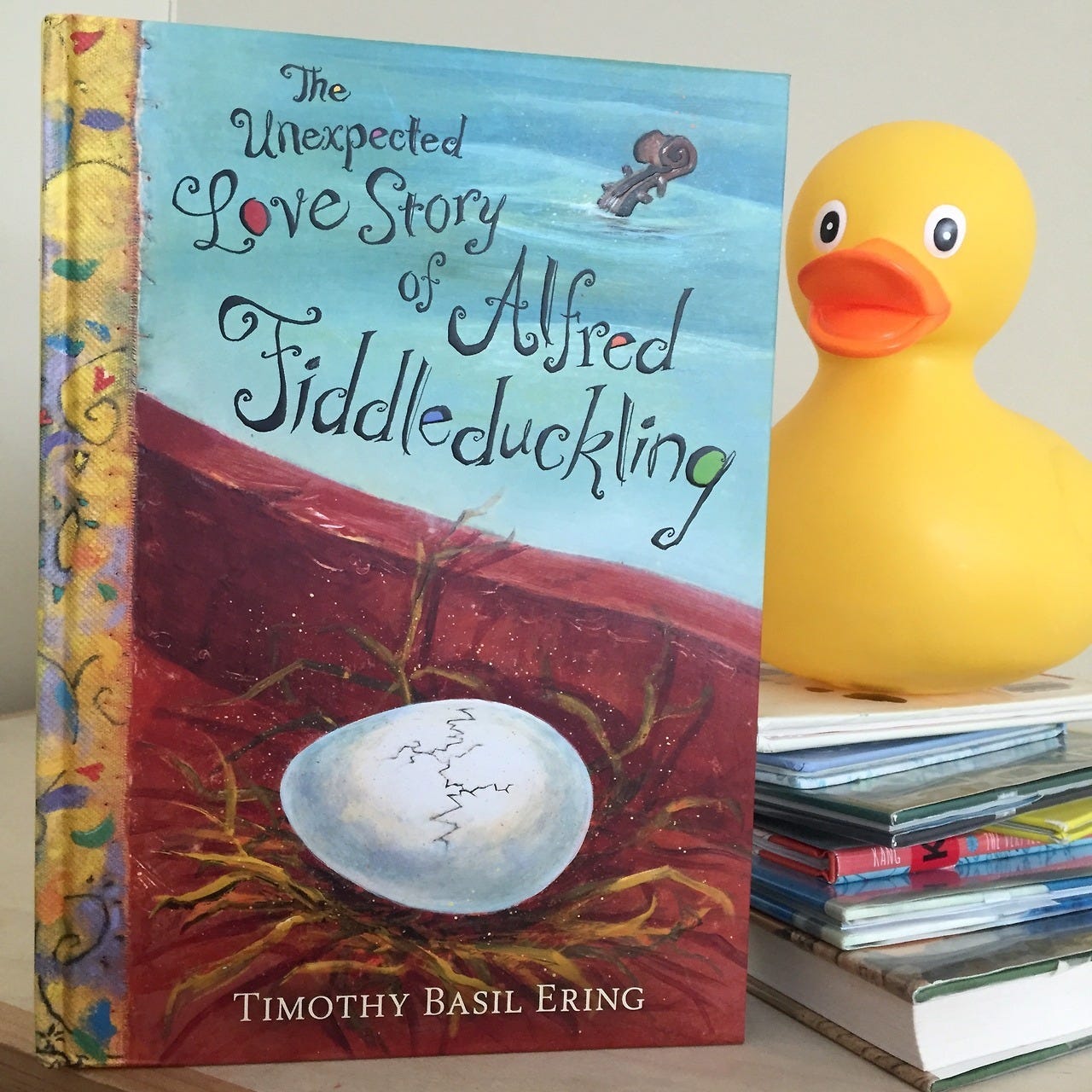

The Unexpected Love Story of Alfred Fiddleduckling

by Timothy Basil Ering

Abrams ComicArts

2017, 240 pages, 6.9 x 1.0 x 9.4 inches, Hardcover

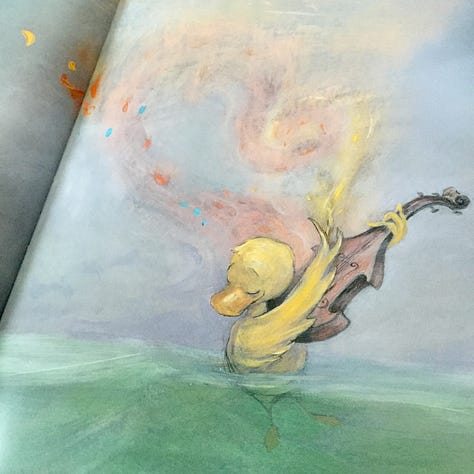

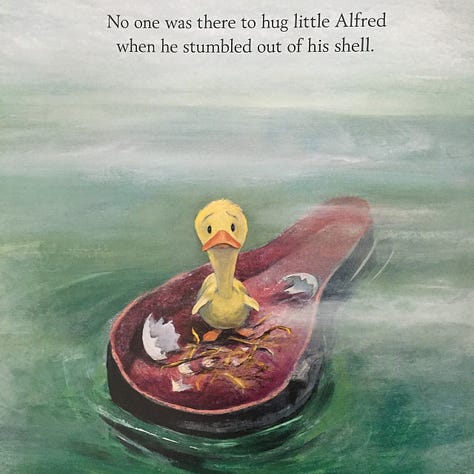

Timothy Basil Ering’s The Unexpected Love Story of Alfred Fiddleduckling is a beautiful book. It is an unconventional, charming love story with a refrain of “unexpected” events and realizations for both the characters within it and the young audience following Alfred Fiddleduckling’s adventures. Ering’s writing is exact and almost understated at times (“It was a storm. A big one.”), illustrated with paintings that are steeped in mood, sea fog, and the light of music.

Alfred Fiddleduckling got his name when he was still an egg, nestled safely in Captain Alfred’s fiddle case, a special gift for the captain’s wife on a journey home across the sea. His namesake (who, in addition to being a fiddler and a sailor, is also a farmer), is on his way home from procuring some new ducks when a storm blows in unexpectedly, leaving Alfred Fiddleduckling to hatch alone and adrift in the empty wet velvet interior of the fiddle case. He imprints on the only object floating nearby, the fiddle. But, unlike the traditional newly hatched bird finds and blindly follows a mother, no matter what creature she may be plot, Alfred Fiddleduckling and the farmer’s fiddle develop a different and deeper instant connection, a relationship that truly sings. Through the music they make together, the duckling and his instrument inadvertently pick up the broken pieces of the shipwreck and bring their ragtag flock back together.

– Mk Smith Despres